On Cowboys

Richard Prince on the genesis of rephotography and the Cowboy series

The following excerpt has been taken from the transcript version of Richard Prince - Deposition (2025), with slight edits for clarity. On view from April 17, 2025 to July 25, 2025 at Sant’Andrea de Scaphis, Deposition (2025) is a 6 hour, 47 minute video from the United States District Court, Southern District Court of New York, recorded on March 23, 2018, when Prince was being sued for copyright infringement over the 2014 exhibition New Portraits.

In Deposition (2025), Prince is questioned in-depth about the origins of his artistic practice. What follows is an unprecedented look into the birth of Prince’s iconic Cowboy series in the artist’s own words.

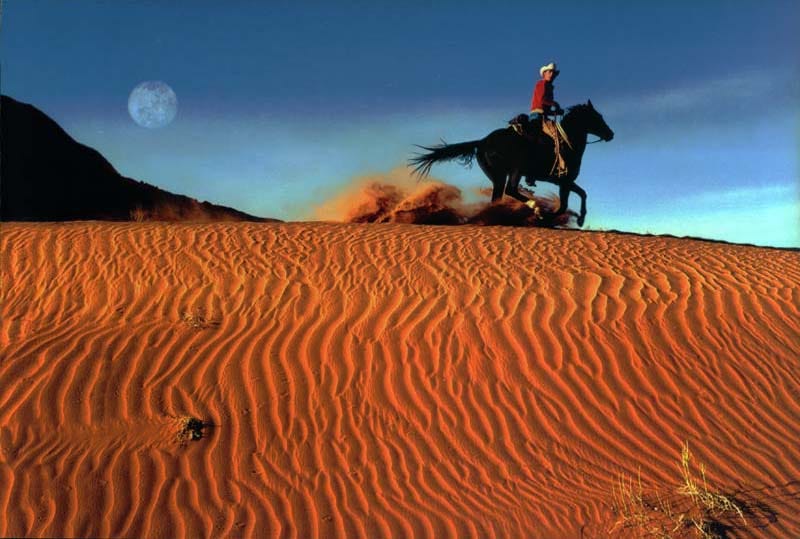

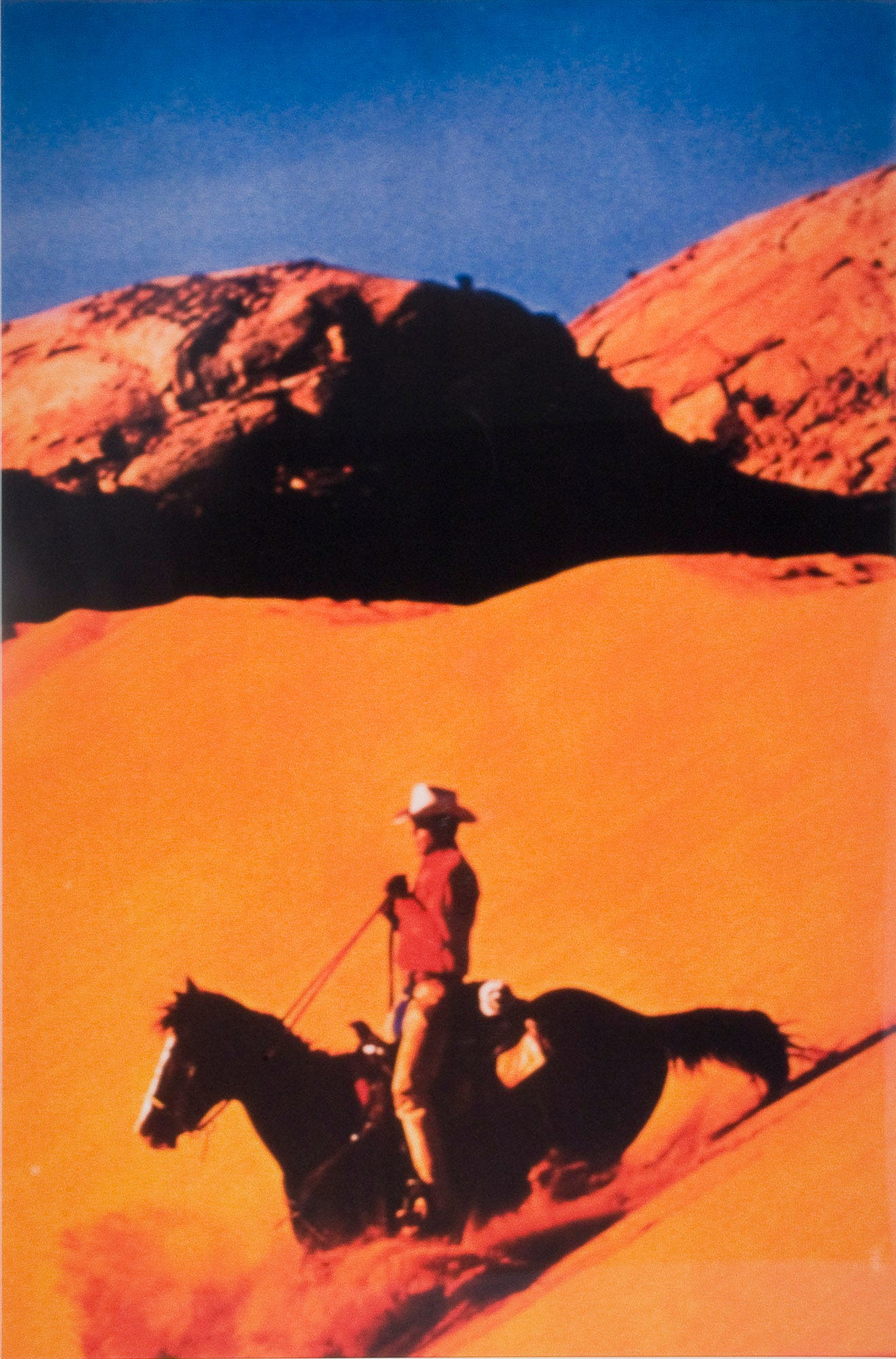

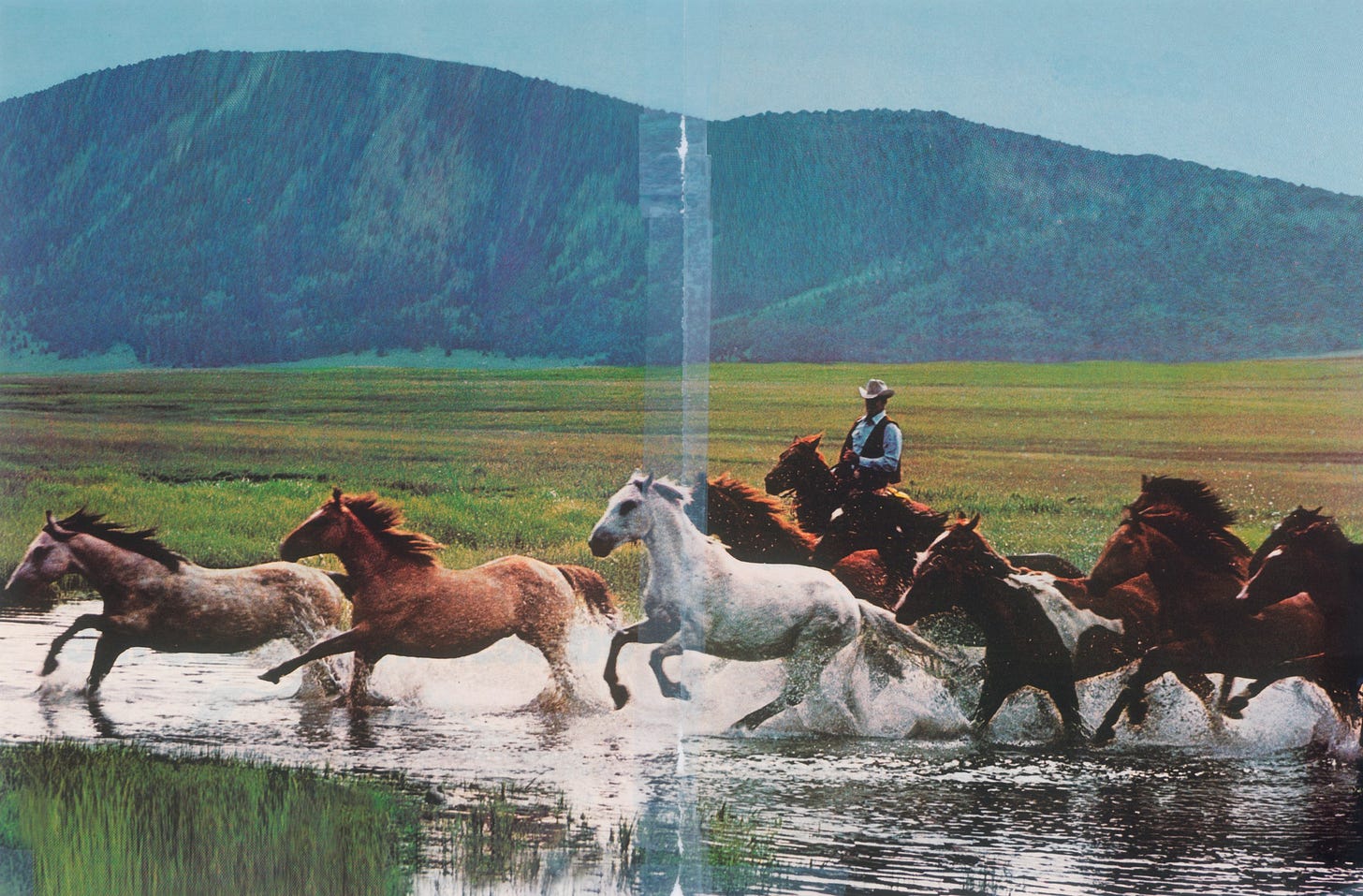

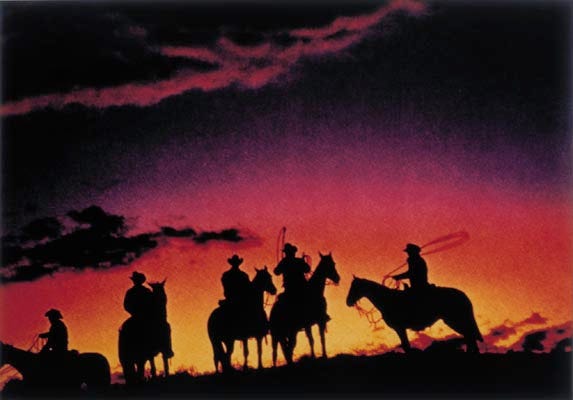

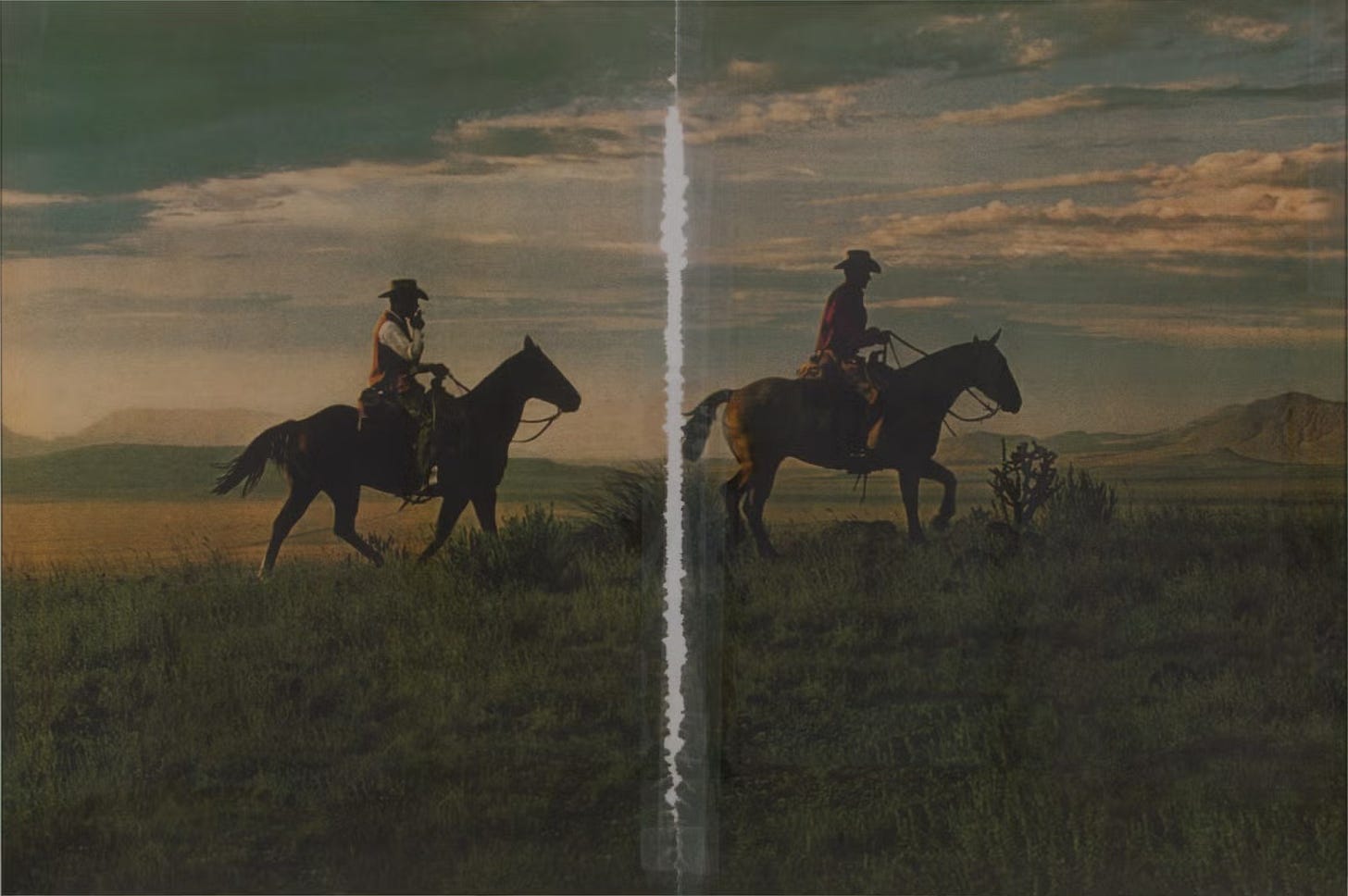

”The Cowboys were images that appeared while I was working at Time-Life. Time-Life at the time was publishing seven magazines. They came out on Mondays.

And my job at the time, at copy processing, was to process all the editorial, and at the end of the day, what was left was the advertising images. Those were not processed, those were left on the desk.

And I started looking at them, and essentially it's a page in a magazine, a cowboy.

This started about 1980, I remember collecting them, because nobody called for them. In those days, editorial was called hard copies, and my job was to make sure that the author of the editorial got his hard copy.

But nobody ever called for the cowboy pictures.

So, I just started putting them in a file and I started making collages out of them.”

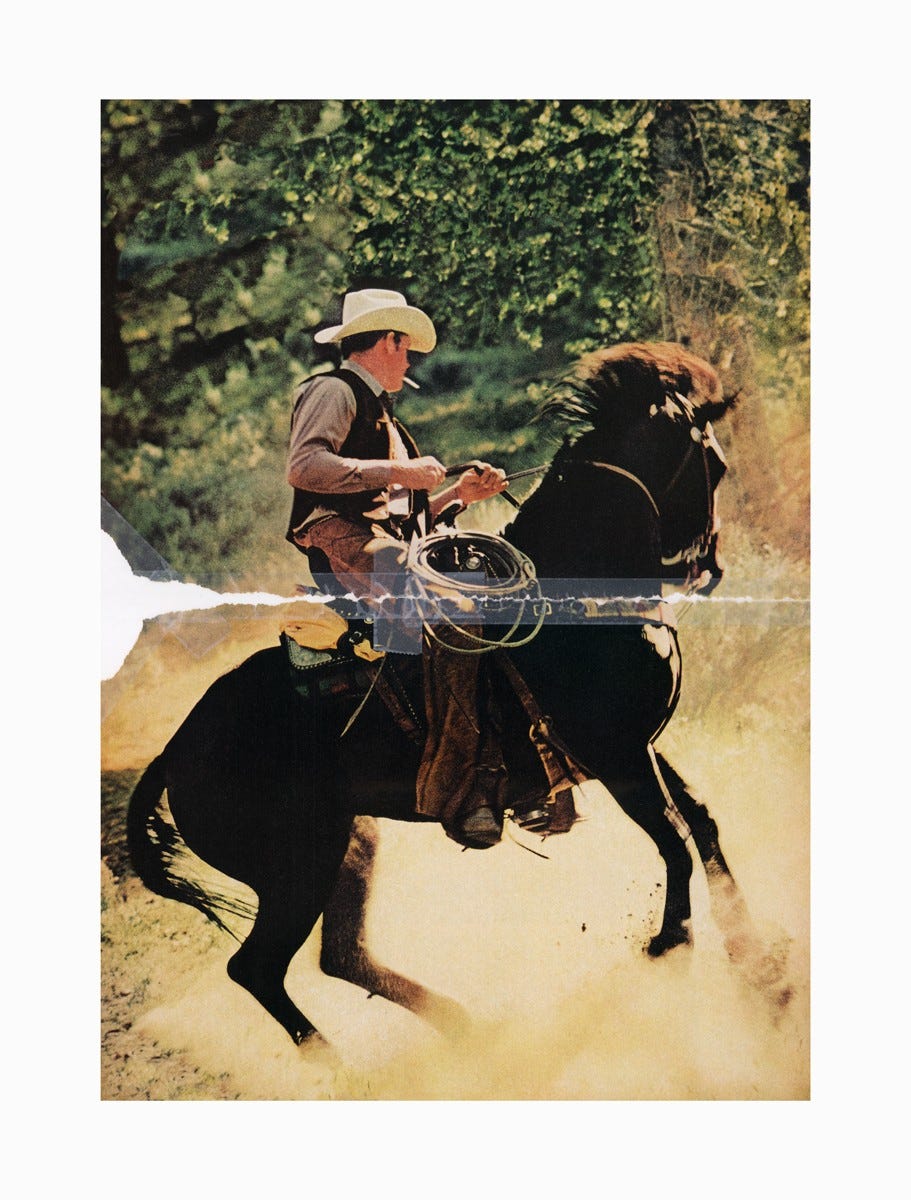

“Collage goes back to perhaps 1903 or 1908, I don't know the particular date, but collage was invented by Picasso and Braque, a really revolutionary way to make new art. But collage has been around now for 100 years.

And I started using scissors and Scotch tape and I would just make collages out of these cowboy images. I never really thought about who owned them or who took them. They were ophalist pictures.

My imagination, my creativity kicked in, and one day I pointed my camera at them, and that's when history happened, 1980. I changed art history, because what I did when I pointed my camera is I turned my camera into an electronic scissor.

When I made an exposure, it was no longer a collage. And I also changed the history of collage.”

“I made what was essentially a page torn out of a magazine, I made it into a real photograph. And I believe my contribution is something that was new at the time.

I came up with the term rephotography. It had never been done before.

And I remember thinking that my camera, this mechanical apparatus that I imagined to be an electronic scissor, was a new way of dealing with collage. You no longer saw the Scotch tape, you no longer saw the tear or the seam, I got rid of all of that.”

“I also realized much later that I got rid of the decisive moment. I changed the history of photography that day. The decisive moment, it was, no longer had to do with luck, you know.

I wasn't a journalist, I wasn't a commercial photographer, I was an artist using the camera.

I didn't really know much about the camera at the time, I didn't know much about a darkroom, but what I did know was I wanted to make what I was collecting into a photograph.

And photographs, the medium has what I called an inherent meaning; you tend to believe a photograph.”

“The interesting thing about rephotography is that if you point a camera at an existing public image that you have torn out of a magazine, you point at it in the morning and you look through the viewfinder, you can walk away and come back that afternoon and you can look through the viewfinder, and the same picture will still be there.

It will never move. There is no chance. Your image is not based on luck anymore, you know.

You're really changing the whole history of Robert Capa, you're really changing the history of the medium.”

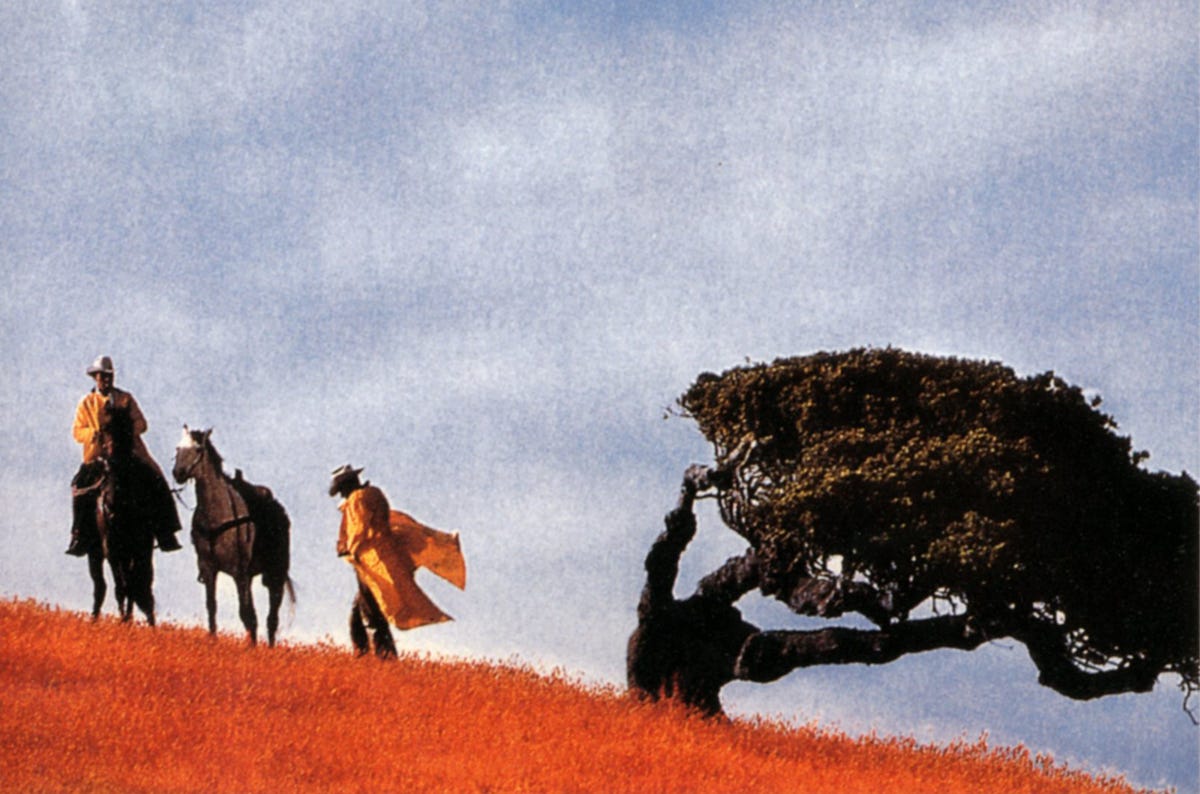

“I believe that it’s interesting, to have worked at Time-Life, to then get a call from Time magazine, just maybe four years ago, to say, ‘one of your Cowboy pictures has been chosen as one of the 100 most important photographs ever taken in the last 100 years.’

I mean, to make history for any artist, it's very difficult to be the first, and I believe that's what rephotography did.

I was a kind of pioneer. No one had ever done it before. It was very difficult to even define at the time, and believe me, it's interesting to look back at the first Cowboy show in 1984, when I hung those rephotographs of the Marlboro images up in a gallery, not one of them sold.

Not one. I didn't make a dime. And it was interesting to get a phone call in the middle of the night that, I believe it was 2006, that I got a phone call, and it simply said Richard, one of your Cowboy photographs just went for over $1 million.

I was the first artist to sell a photograph for more than $1 million.

I received a phone call at 10:00 at night, I was asleep. I said, ‘Oh, okay,’ and I hung up the phone and I went back to sleep. I thought, a little bit like Roger Bannister, it's something that will never be able to be taken away from me.

And I believe it was a bit of irony—I think that's the word, simply because as I thought about 1983, the fact that no one bought, no one cared, no one knew what I was doing.”

“No one knew what I was doing because I didn't ask permission.

I gave myself permission, and in order to create history, in order to really create incredible, fantastic art that makes people feel good, because ultimately that's what, all I really want to do, is to make people feel good, you don't -- why would you?

You can't ask permission. You just have to go ahead and do it.

You have to have guts to make great art.”

“My, for lack of a better word, mentors, the artists that I look to, are the people who made history: Braque, Picasso, Jackson Pollock. It's just indescribable what he did in 1942. And the same thing with Andy Warhol1. I mean, imagine painting, a Campbell's soup can, I believe it was 1961. I mean, did he ask Campbell's? Did he call up?

No, he was actually eating the Campbell's soup every day for lunch, That's why he painted it.

Artists oftentimes find the best subject matter in what's right next to them, what they do every day. I believe that's what happened with the Cowboys. They were right next to me every day. Every Monday I looked forward to the magazines being published, because I would quickly go through them and, look, oh, is there going to be a new cowboy advertisement?

It was exciting. It's hard to describe, but I was also working, and I turned that job at Time-Life, which was this great dystopian building2, open 24 hours a day, seven days a week, kind of a JG Ballard3 type of situation, I turned it into my studio.”

“And yes, usually the idea of appropriation does start outside yourself. And it's important to me at the time that the issues that my generation was dealing with, growing up, we were the first generation to grow up with TV. We were the first generation to grow up in the Cold War, we were the first generation to question truth. I mean, what was the truth? What was really? What was not real? I mean, think of it.

What was a lie? What was not a lie?

These were the issues we were dealing with. And I believe that I, at the end of the day, even though I was tearing - my job was to give the editorial, I, at the end of the day, I started believing in the advertisements.

I actually believed that the cowboys were more real than what the rest of the world thought was real.

I mean, that's how -- that's the only way I could deal with reality at the time.”

“It turned out that great art in the end is agreed upon. And that's a difficult situation, that's a difficult thing, to ask to have consensus.

Art is not necessarily in the eye of the beholder. I think we can agree that Picasso was a great artist. I don't think there is an argument.

I mean, I know art is subjective, but what I'm trying to do, and what I've always tried to do. I don't think the Cowboy photographs are subjective anymore.

I have a retrospective of The Cowboys up right now at one of the most prestigious institutions in America at LACMA, Los Angeles County Museum4.

And there seems to be some sort of agreement, finally, and when you are talking about criticality or a critic, that's something I don't pay attention to. What I pay attention to is the time. It takes a long time for a number of people to agree on whether an artwork will last, will have any relevance.

And I think what's interesting about rephotography is to think of what I did in 1977, and then think of what's happening now in social media.

Everybody is taking photographs. And are they asking permission? Do they need to ask permission?”

Richard Prince - Deposition (2025) is on view in tandem with Jannis Kounellis - Untitled (Muro d’oro) (1986) at Sant’Andrea de Scaphis until July 25, 2025.

The retrospective was on view at LACMA from Dec 3, 2017–Mar 25, 2018.